|

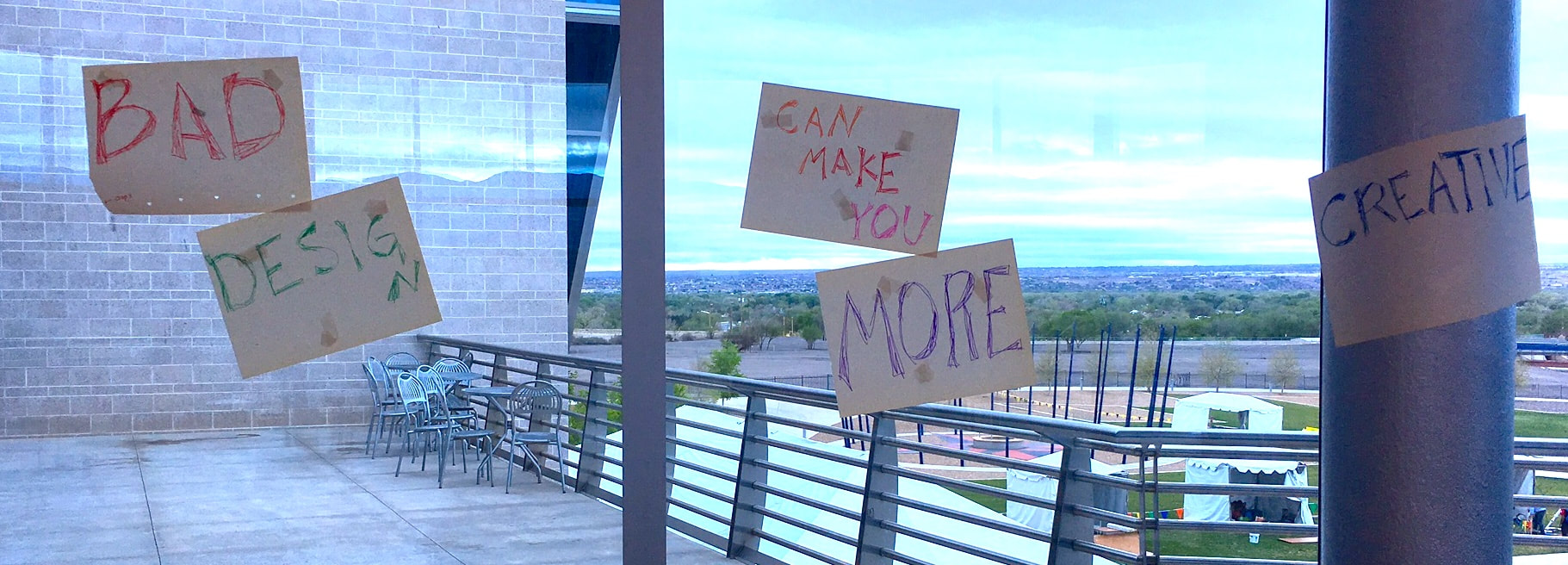

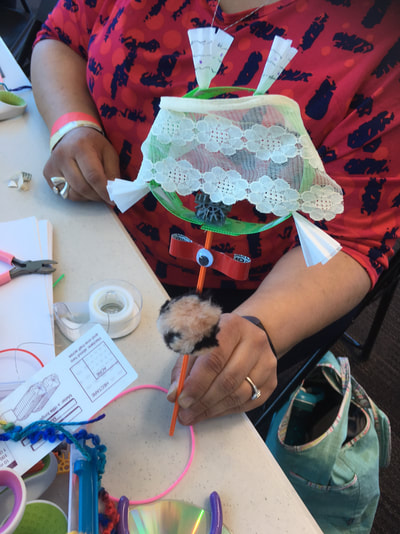

With students from my Creativity and Technical Design course, I presented all weekend at our MakerFaire. We had lots of great conversations about how and why wrong theory works. We brought some simple design challenges for people to try:

We brought lots of materials for people to prototype with. And mostly, they ignored the design challenges and just had some fascinating material conversations. A few insights, that I will carry with me as I work on my CAREER project:

1 Comment

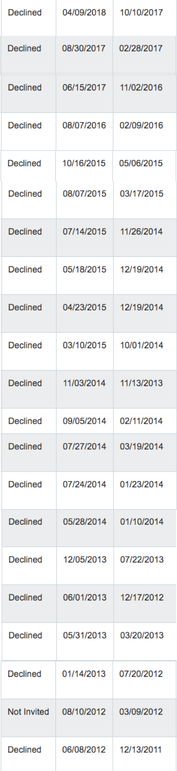

It's AERA 2018, which feels like it was forcefully smashed into the middle of Manhattan. I am not doing great at getting to sessions or events. Everything feels like effort, and some of that is because I am exhausted from teaching a too-heavy load. But this post is supposed to be about framing and agency. So let's talk about the term "teaching load," and how that term frames our work. We don't generally speak of "research loads" though I have heard of "service load" and "administrative load." Why are these heavy things? And how agentive are these terms? How often do we speak of carrying a certain teaching load? More often, I say/hear "I have a X/X teaching load," or "I have a heavy service load." And when we get a reduced teaching load, it is "I got a course release." So these carry a sense of ownership, but more like saying "I have blue eyes." I didn't do anything agentive to get eyes that color. I do not have locus of control. How does framing everything but research as loads make us think of these activities? And especially in light of the fact that the NSF CAREER program specifically calls upon us to integrate research and education activities?  Speaking of the NSF CAREER award, and the idea that research is somehow different from the rest of our work... Word has begun to spread that I have been the recipient of two significant early career awards. In 2014, I was the first person at my university to be awarded the National Academy of Education / Spencer Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship. And each time I attended the Spencer reception at AERA, other attendees accused me of crashing it. Framed as an imposter. But this year, all that changed. Three different people introduced me to others as a role model. Reframed as a success. And so I want to take that framing—role model—and do it justice. In talking to senior scholars, I see some of them making some attribution errors about their success in getting grants. Just like in banking, it takes money to make money, the rich get richer. When I hear someone senior talk about getting most of the grants they submit, I am happy for them, especially when they are putting junior scholars on as co-PIs, getting them started. It's a bit like parents who start a bank account for their kids. As a junior scholar who was going it alone for the most part, or with a band of other unknowns, I think it is important to say this: my success stands atop a huge pile of fail. I have been involved with 12 successful external grants in which I had some sort of framing agency; of those, I have served as a co-PI five times and PI only twice. And I have had 24 proposals declined, mostly by NSF. In an annual review letter, someone called me "tenacious." So you can see what a huge pile of fail looks like, here is the list of declined proposals in my NSF proposal status window. After a number of years flailing about, I found an established scholar—the chair of Chemical Engineering at UNM—who put me on as co-PI. And my success rate has definitely increased since then. So if you ask me for a copy of a grant proposal, I will happily give it to you. I am open access like that. And as I climb, I commit to helping others up. I'll take that framing of role model, thank you very much. The best thing about being at AERA is that the R really stands for reunion, not research. In my CAREER proposal, I included "peer thought partners" and this is one of my favorite things I did. These are the people who know my work, who think with me, who push me, who inspire me. Michelle Jordan is one of them, and we had a great, late-night conversation about strategies for a successful sabbatical—on shifting from being productive to being progressive. And that takes some major framing agency to do. We spend a lot of time saying "yes" to things. That comes at a cost, in terms of being able to think deeply and make good progress on things we care about.  Another peer thought partner is Brian Gravel. I snapped this conference selfie just before our talk, which drew more attention than I'd hoped it would. I got way too much of the screen and cut his face in half, but it is so joyful, and it captures how I feel about working on our paper together. In trying to understand framing agency, we bumped up against other forces in design. First, and most obvious, but not exactly the focus of the talk we gave today, is that sometimes designers display low agency to invite others into a design problem space.  Second, is the idea, as has been discussed by others, that materials talk back to designers. We are working on characterizing the range of those conversations. Third, we are introducing the idea of a conjured user. In responding to a question after our talk, I mentioned that we sometimes see a designer conjure a user into the space, and then sometimes shift, as if letting the user take possession of their body, making possible arguments of use. I really like where these ideas of framing agency are taking me, and that they are taking me places with others.

|

Vanessa Svihla, PhDAssociate Professor, Organization, Information & Learning Sciences Archives

October 2019

Categories

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. EEC 1751369. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed