|

It turns out that I am terrible at blogging. Not that the posts are terrible, but actually posting seems to be the first thing to not happen when there is too little slack in the system.

This semester, I am teaching 4 courses (two of which are two sections of the same 1-credit course, but still), I have 6 doctoral students progressing through comps or proposals (plus am on committees of two others doing so), and I am the 'reluctant' acting program director while my counterpart is on sabbatical. So there is little slack in my system. And when crises strike—always related to the program director role—it is very clear there is too little slack. Something does not get done. And because I study problem framing and creativity, I know I can work efficiently, I can still adaptively reframe problems on the fly when needed, but not with the level of creativity that I could if I have a bit of time to reflect and ponder. I am grateful for this capacity, but I crave thinking time, which is teasing on the horizon (71 days until sabbatical!!!!!). So why I am writing, with so little time, so little slack? Just like in the movie, The Matrix, the secret to bending the spoon—or finding time to reflect—is a matter of belief. There is no spoon. There is no to do list. A former grad student would have referred to it as mindfulness. It feels more like willfulness. Choosing to sit here at my dining room table on a rainy fall morning, and grasp a moment to think.

Today I am thinking about measuring framing agency—in talk and with surveys. This week, with my amazing doctoral student Amber Gallup, we are pilot testing the survey, and with my wonderful collaborator, Ardeshir Raihanian Mashhadi at University of Buffalo, we are testing ways of automating detection in talk, heavily informed by my discourse analysis.

And I am reflecting on framing agency as an ontological innovation (diSessa and Cobb, 2004), as theory that should cut nature at its joints ("division into species according to the natural formation, where the joint is, not breaking any part as a bad carver might" Plato, 360 BCE, http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/phaedrus.html). People have responded to framing agency in ways that make me think it is not only new, but needed, that it helpfully draws attention to a joint. It is a terrible metaphor for a vegan to use, of course, and one that has been critiqued by scholars, of course, who argue that nature is not jointed (https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/carving-nature-its-joints), and therefore joints are not waiting to be "discovered." I agree wholeheartedly with this critique of discovery-based views. When I first began writing about problem framing, it felt like screaming to the void. People kept asking if I meant "problem solving?" No. When I referred to 'finding and framing problems" people got excited about the "finding" part. I think it is because we all wish there was some magic bullet that will help us have insight without effort. Framing problems is effortful. Finding problems is an act of brilliance, and one that I don't think is worth committing time trying to investigate that much because so much is made covert by phrases like "finding" and "discovery." I am much more interested in the effort. In the framing, and laying bare all that effort that goes into it. "Finding" framing agency has taken years of effort. It is itself a framing process. And I am writing this morning—making slack—for effortful thought. This is a short post about naming proposals/projects. I like to have a short, pronounceable title that hints at the project in some manner. I have mostly succeeded at this, and here are the tools I use:

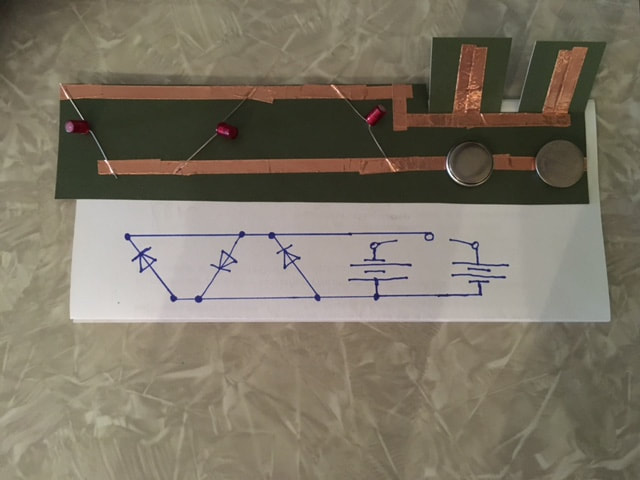

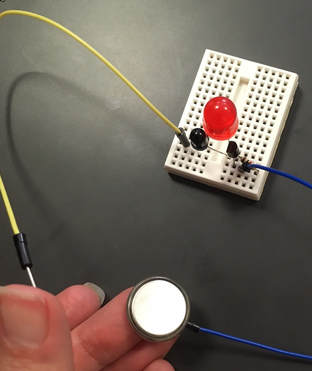

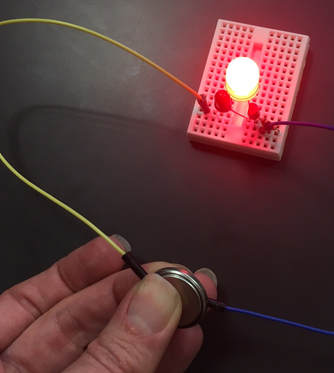

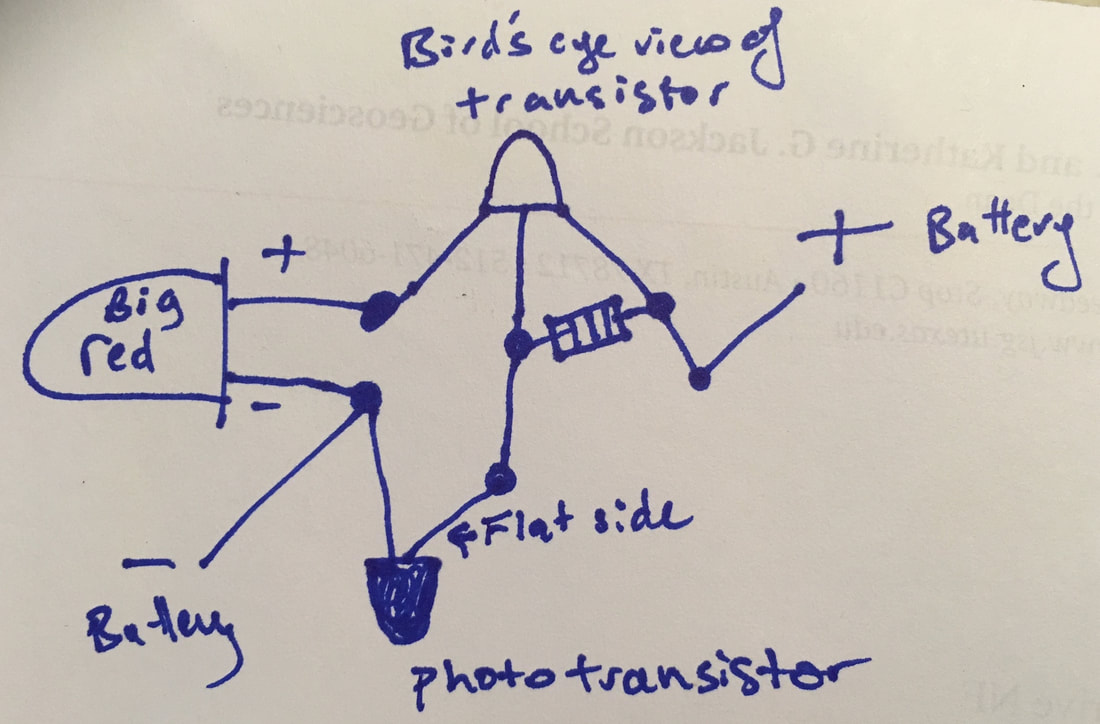

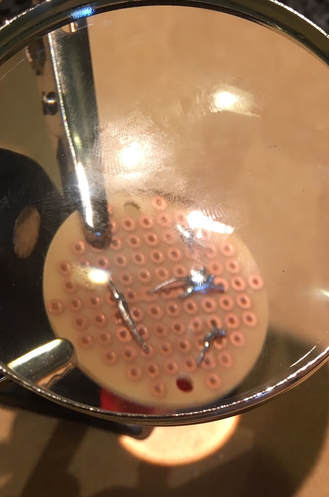

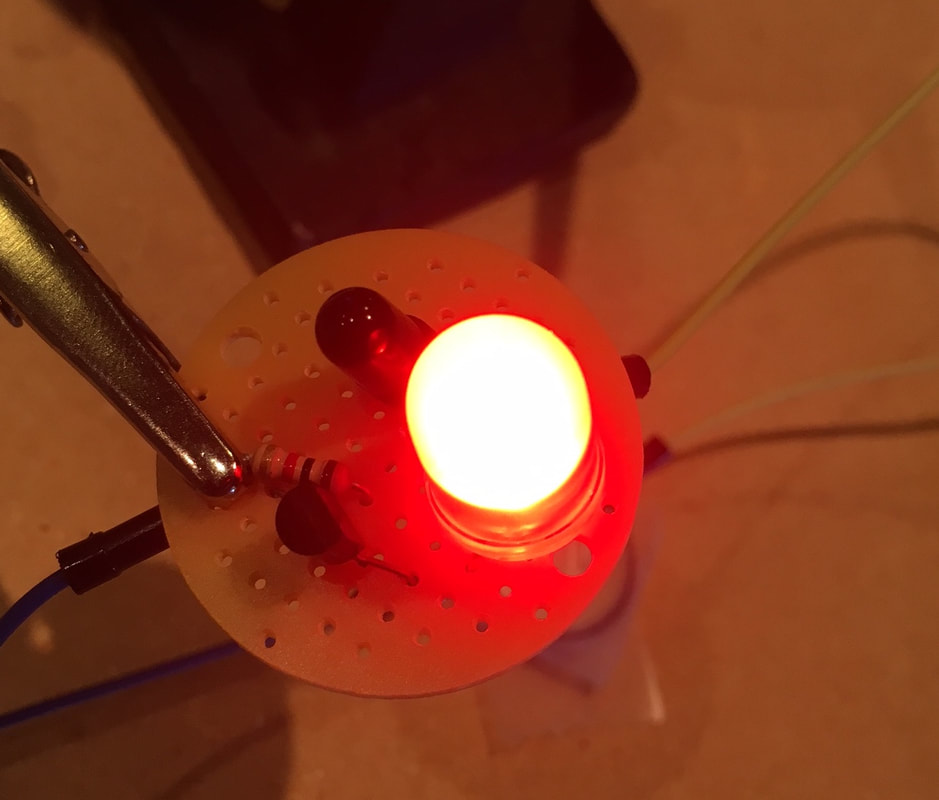

1. OneLook search: If you have part of an acronym figured out, and need to fill in the rest, you can do a wildcard search with "*." For instance, if you were looking for a word that included the existing set of letters "CAR" you could search "*car" and "car*" https://www.onelook.com/ 2. RhymeZone search: Look for words that rhyme with a word you plan to use as part of the title. This is the one I turn to when a bit stuck, when I have a set of letters that I am having trouble turning into a word. https://www.rhymezone.com/www.rhymezone.com/ 3. Anagram maker: If you have a set of words you want to incorporate, then you also have a set of letters. If you include at least one vowel, and you think you can phase your title in several ways, the anagram maker is a good option. https://wordsmith.org/anagram/ If you need to buy a vowel, consider using a thesaurus with your key terms https://www.thesaurus.com/ 4. Some people use the backronym approach. For instance, our FACETS project, we named a conference room CRISTAL then came up with what it stands for (Center for Research Into the Scholarship of Teaching And Learning). Sadly, I have not found a good, configurable online generator. 5. When possible, avoid lowercase letters and weird misspellings. This is not always easy (like in our CRISTAL example above), but know that people will struggle to write it—and even pronounce it correctly. 6. When inventing a word, because it is pronounceable, make sure to do a search and see what else comes up. You don't want your research project on empathy and peace studies to also be a reference to a white supremacist group! Likewise, when inventing words, see if people are willing to say them. Some words just sound weird. I like these titles because it gives a quick shorthand for referring to specific projects, makes it easy to use in file naming protocols, and provides some sense of identity. When I have been on new teams, and we are doing what should be a simple task like scheduling a next meeting, sometimes deciding what to name the meeting takes longer than it should. This suggests that you don't have a pithy-and-sticky way to refer to your work together, and that you don't know what the project is really about (which is perfectly fine for early stage work). I started this post over a year ago (!), but am just now getting to posting it—testament to my inconsistent blogging habits. With a sabbatical coming up this Spring, I hope to get back to this kind of writing, to share some recent developments on this project. I have been thinking about agency and materiality in relation to understanding and experience quite a bit lately, and how these relate to diversity and creativity. The tricky thing is this: 1. What you know about materials gives you ideas for what the materials "should" do—their being/doing potential. Expertise constrains thinking, and this is well known. 2. When you don't know what the materials are for, it seems easier to have becoming material conversations with them, but it can be hard to have functional, feasible ideas. For instance, I have been teaching myself circuits and so forth. I really like working with copper tape and LEDs. In the process of trying to make a light-up art piece (not shown in the video), I wondered what would happen if I put an LED in the wrong direction, and then that made me wonder what would happen if I also added an extra battery and switch. What did I know, that led me to design this circuit? First, I knew that LEDs are diodes, and diodes have polarity, meaning the current can only flow one direction. I did not know, however, if having two batteries might somehow break my circuit. Not only have my circuits-on-walls been a resource for students, they have also inspired others. A researcher who works with Arduino was visiting my lab and was struck by these, both as a teaching tool and as a jumping off point. He said the next thing he would do is add photoresistors. So that afternoon, I googled how they work. When I hold my flashlight up to the photoresistor, the circuit comes on, which is a kind of sad circuit, if you don't know to do that. And having a light come on if you shine a light on it seems useless. So that got me thinking about (1) other circuits that could be turned on by a photoresistor and (2) making a dark detector. After a bit of googling, I found the following: https://www.evilmadscientist.com/2007/a-simple-and-cheap-dark-detecting-led-circuit/. I found supplies that looked like what I needed. Since I was not sure if they were the same, I used a small breadboard to prototype. With a bit of assistance from my student Chen in reading (1) the circuit diagram and (2) the tiny numbers on the transistor, we got it to work! Next, I drew my own diagram, since the circuit symbols are still a bit unfamiliar to me, and I was a little unsure of a couple parts—in part because of Chen's assistance. Next I got my solder station set up and began moving components from the breadboard to a little round perfboard I had. I forgot to bring a battery holder home, so I'll have to figure that part out another time, especially given that the phototransistor needs day light to turn off—indoor light does not cut it. Next one to try: http://www.buildcircuit.com/darklight-sensor-using-transistor/). I think this one will work in a broader range of indoor lighting. And there are some interesting ways to use it with Arduino: http://www.oomlout.com/oom.php/products/ardx/circ-09 Maybe there is a Goldilocks spot in the middle—a shifting target for innovative work to happen as we learn? That idea is comforting for those still learning because it invites participation!

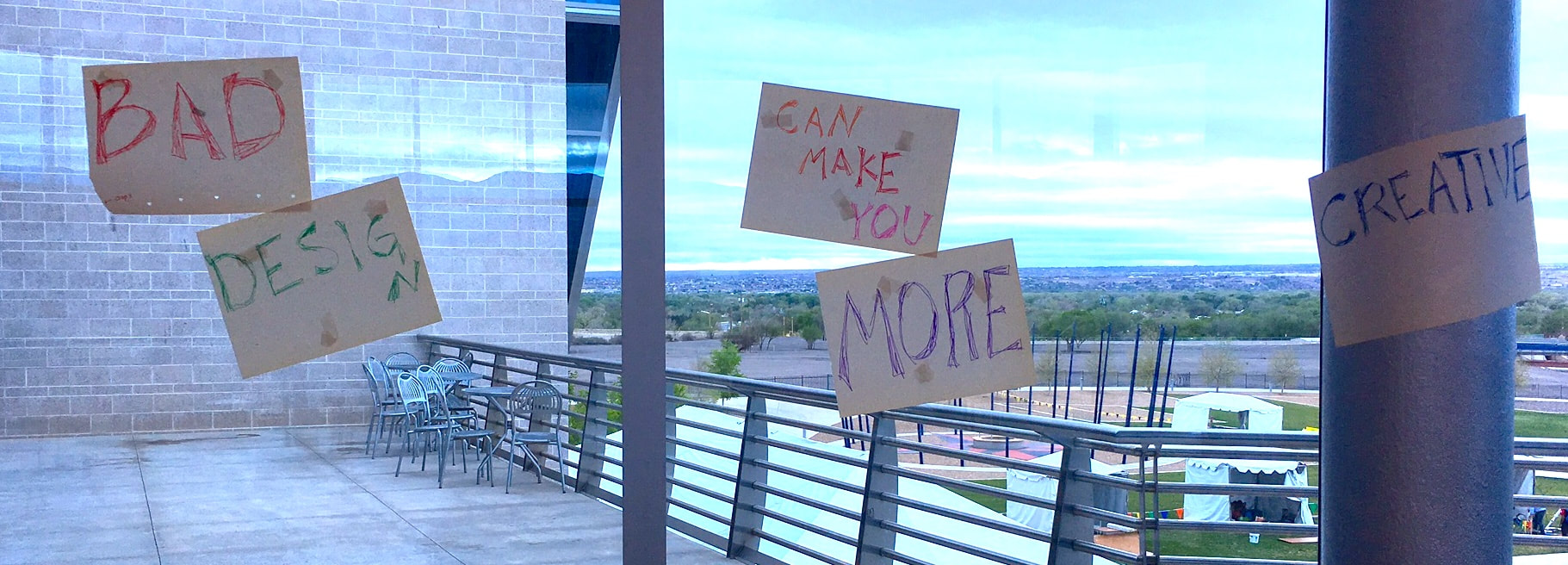

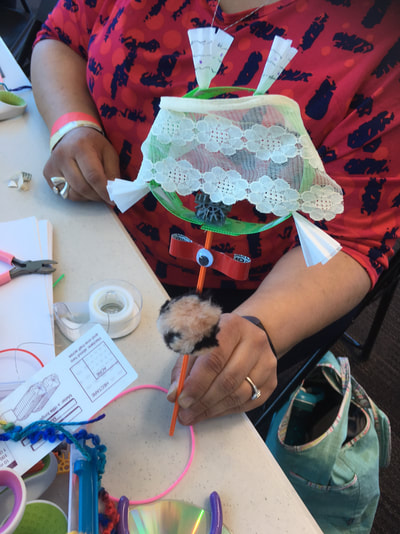

With students from my Creativity and Technical Design course, I presented all weekend at our MakerFaire. We had lots of great conversations about how and why wrong theory works. We brought some simple design challenges for people to try:

We brought lots of materials for people to prototype with. And mostly, they ignored the design challenges and just had some fascinating material conversations. A few insights, that I will carry with me as I work on my CAREER project:

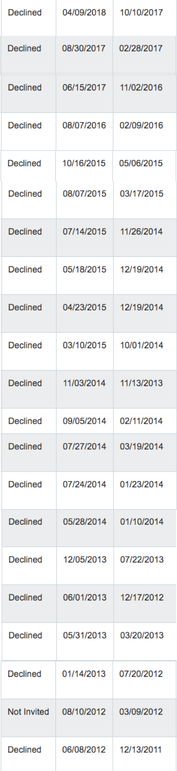

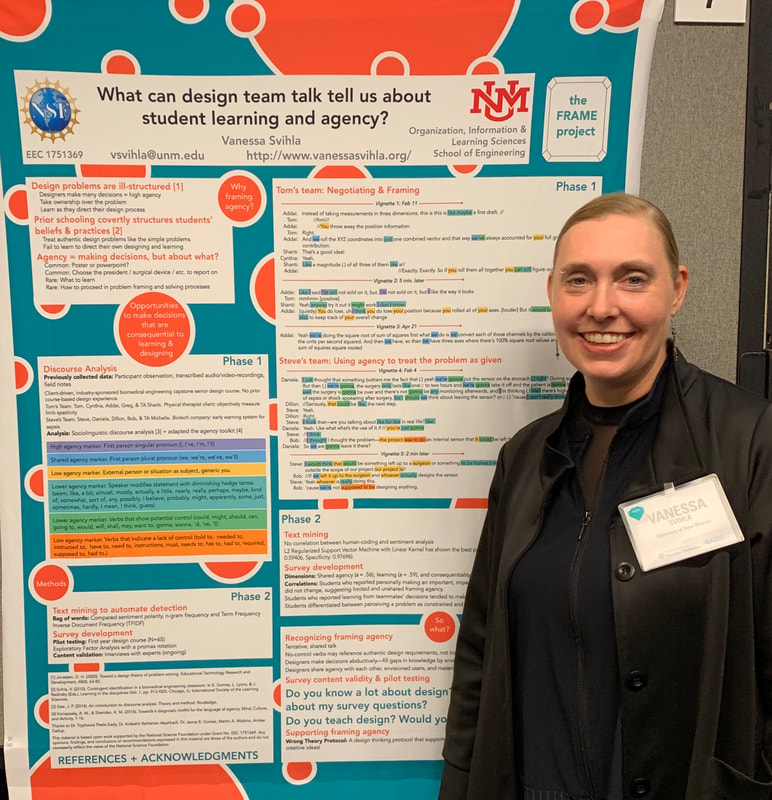

It's AERA 2018, which feels like it was forcefully smashed into the middle of Manhattan. I am not doing great at getting to sessions or events. Everything feels like effort, and some of that is because I am exhausted from teaching a too-heavy load. But this post is supposed to be about framing and agency. So let's talk about the term "teaching load," and how that term frames our work. We don't generally speak of "research loads" though I have heard of "service load" and "administrative load." Why are these heavy things? And how agentive are these terms? How often do we speak of carrying a certain teaching load? More often, I say/hear "I have a X/X teaching load," or "I have a heavy service load." And when we get a reduced teaching load, it is "I got a course release." So these carry a sense of ownership, but more like saying "I have blue eyes." I didn't do anything agentive to get eyes that color. I do not have locus of control. How does framing everything but research as loads make us think of these activities? And especially in light of the fact that the NSF CAREER program specifically calls upon us to integrate research and education activities?  Speaking of the NSF CAREER award, and the idea that research is somehow different from the rest of our work... Word has begun to spread that I have been the recipient of two significant early career awards. In 2014, I was the first person at my university to be awarded the National Academy of Education / Spencer Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship. And each time I attended the Spencer reception at AERA, other attendees accused me of crashing it. Framed as an imposter. But this year, all that changed. Three different people introduced me to others as a role model. Reframed as a success. And so I want to take that framing—role model—and do it justice. In talking to senior scholars, I see some of them making some attribution errors about their success in getting grants. Just like in banking, it takes money to make money, the rich get richer. When I hear someone senior talk about getting most of the grants they submit, I am happy for them, especially when they are putting junior scholars on as co-PIs, getting them started. It's a bit like parents who start a bank account for their kids. As a junior scholar who was going it alone for the most part, or with a band of other unknowns, I think it is important to say this: my success stands atop a huge pile of fail. I have been involved with 12 successful external grants in which I had some sort of framing agency; of those, I have served as a co-PI five times and PI only twice. And I have had 24 proposals declined, mostly by NSF. In an annual review letter, someone called me "tenacious." So you can see what a huge pile of fail looks like, here is the list of declined proposals in my NSF proposal status window. After a number of years flailing about, I found an established scholar—the chair of Chemical Engineering at UNM—who put me on as co-PI. And my success rate has definitely increased since then. So if you ask me for a copy of a grant proposal, I will happily give it to you. I am open access like that. And as I climb, I commit to helping others up. I'll take that framing of role model, thank you very much. The best thing about being at AERA is that the R really stands for reunion, not research. In my CAREER proposal, I included "peer thought partners" and this is one of my favorite things I did. These are the people who know my work, who think with me, who push me, who inspire me. Michelle Jordan is one of them, and we had a great, late-night conversation about strategies for a successful sabbatical—on shifting from being productive to being progressive. And that takes some major framing agency to do. We spend a lot of time saying "yes" to things. That comes at a cost, in terms of being able to think deeply and make good progress on things we care about.  Another peer thought partner is Brian Gravel. I snapped this conference selfie just before our talk, which drew more attention than I'd hoped it would. I got way too much of the screen and cut his face in half, but it is so joyful, and it captures how I feel about working on our paper together. In trying to understand framing agency, we bumped up against other forces in design. First, and most obvious, but not exactly the focus of the talk we gave today, is that sometimes designers display low agency to invite others into a design problem space.  Second, is the idea, as has been discussed by others, that materials talk back to designers. We are working on characterizing the range of those conversations. Third, we are introducing the idea of a conjured user. In responding to a question after our talk, I mentioned that we sometimes see a designer conjure a user into the space, and then sometimes shift, as if letting the user take possession of their body, making possible arguments of use. I really like where these ideas of framing agency are taking me, and that they are taking me places with others.

In October, when I first got the request for a public abstract, IRB approval, and my response to questions, I was thrilled, and went into a frenzy of activity, digging further into discourse and linguistic analysis and survey design. The questions were exactly the questions I would have run into at some point, so to get them so early was immensely helpful. I therefore felt mentored and scaffolded by my program officer, Elliott Douglas (@ElliotPDouglas) and the anonymous reviewers on my panel.

I reached out to some of my advisory board members, who responded quickly, despite the short timeline. Special thanks to Jennifer Bekki, PhD for her detailed feedback and great suggestions about a resource for survey design: McCoach, D. B., Gable, R. K., & Madura, J. P. (2013). Instrument development in the affective domain. Social and Corporate Applications: Springer.

I began my first step, which was to attempt to adapt the agency toolkit for my analysis.

Konopasky, A. W., & Sheridan, K. M. (2016). Towards a diagnostic toolkit for the language of agency. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 1-16.

Abigail presented similar work in a session at AERA 2017, and it resonated with me. Adapting this was productive and fun, if slightly speculative work at the outset. It was a bit of a leap of faith, as this was a new-to-me focus on qual analysis.

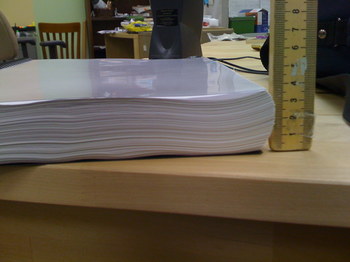

Part of my phase 1 work is to reanalyze existing data, including some of my dissertation data! When I did my dissertation, very few social scientists took the 3-paper dissertation route. As a result, I ended up with ~150 pages of interpreted transcript. While this looks impressive, it was essentially unpublishable work. And very little of that qualitative work has ever made it out of that dissertation. So my first step was to begin coding some of that work.

I was surprised at how well it initially worked. Because of my past as a geologist, I tend to look at longer timescales (weeks, months, years) of learning trajectories, using the tools of interaction analysis and conversation analysis. ‚Äã Jordan, B., & Henderson, A. (1995). Interaction analysis: Foundations and practice. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 4(1), 39-103.

What surprised me was the fractal quality I uncovered. Just as in geology, where the structures observed at the landscape scale are often also findable under the microscope in thin section, here, the patterns I saw over months were also findable in just a few turns of talk.

I reached out to another advisory board member, Dr. Tryphenia Peele-Eady, who directed me to a resource, and quickly diagnosed a dissatisfaction I was having: looking only at the functional linguistics did not fit what I was trying to accomplish. I needed a sociolinguistic approach. Together, we refined the coding scheme and conducted some analysis, which we submitted as a conference proceeding. This process of attempting to clarify framing agency also helped clarify for me that it really is a productive construct. While the two teams we analyzed both made decisions, only one team made designerly decisions. This approach easily differentiated between the two teams. Gee, J. P. (2014). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method: Routledge.

In my proposal, I named several "peer thought partners" who "have a record of pushing my thinking constructively, and who are already familiar with my research." I reached out to one of them, Brian Gravel, and we worked on some analysis, thinking about the ways agency might play out in heterogenous design, a topic on which we are presenting at AERA 2018. We did some productive pushing and prodding on the construct of agency, which we hope to present at ICLS 2018.

Finally, I just want to reflect briefly on this experience so far. It has already pushed my thinking. I feel so privileged to have this opportunity, this push to do work I really want to do. In the busy-ness of academia, it is too easy to set aside some of the good but hard work for the right now work. I am so lucky to have this grant that pushes this good but hard work into the right now. |

Vanessa Svihla, PhDAssociate Professor, Organization, Information & Learning Sciences Archives

October 2019

Categories

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. EEC 1751369. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed